Amidst all the new and cutting-edge art on display at Art Basel and surrounding fairs, an exhibition of late painter Purvis Young’s work is a well-deserved resurrection.

“A Man Amongst the People: A Purvis Homecoming” is the first art show in the newly renovated Historic Lyric Theater in Overtown. The exhibition represents a homecoming for work made by the former Overtown resident.

Young’s art drew on the life and characters of the neighborhood and can be easily identified by his painted figures: emotionless heads, many on squiggle-like bodies adorned with halos. The paintings are full of activity; they are noisy, semi-abstract scenes painted in thick strokes.

They are a perfect example of American “outsider art.”

ROOTS

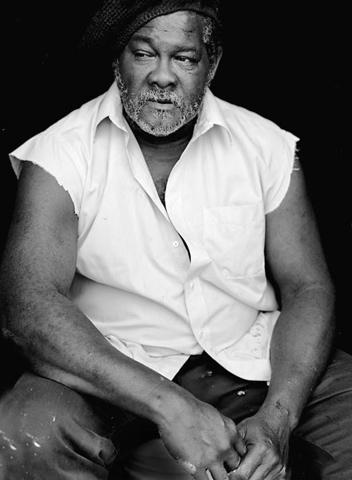

Archivist Dorothy Fields, founder of the Black Archives, remembers Young not as an internationally known painter, but as a neighborhood character who covered the exterior walls of shotgun houses with paintings.

“We used to laugh at him,” she recalls, “seeing this guy painting on the wall.”

At the time, she and her high school peers found his paintings weird.

Overtown, the once vibrant black neighborhood near downtown Miami, deteriorated after a lot of it was bulldozed to make way for highways during the 1960s. It was a slow disintegration that Young saw and painted.

“He was very much interested in the political aspects of the community,” says Fields. “He was concerned about the trucks that come through. He was concerned about I-95. … He was very much interested in what was going on around him.”

Among those surroundings were the people – prostitutes, families, drug dealers and kids — and their struggles in the impoverished neighborhood.

WORK

For Purvis Young, the walls that Fields saw him paint weren’t his only canvas. He would paint on anything and everything: plywood, rugs, manila folders, doors, even tabletops.

“One things about Purvis’ work is you got to be careful of the nails, staples, splinters, wood. You have to very carefully handle his artwork,” says Timothy Barber, curator of the show. He did his bit to install some of the work.

Barber points to one painting in particular that incorporates scrap plywood and rubber-coated electrical wiring. Several strips are laid out vertically, like prison bars. The lines separate the viewer from what Barber describes as a “festive scene.”

Young spent three years in prison as a teenager. Though there are mixed accounts of what exactly landed him there, he attributes those years to finding art as a means of expression. Prison was also one way he viewed the neighborhood, a place people tried to escape. Horses are a common symbol in Young’s work. To him they were the epitome of freedom, a means to escape the trucks and tanks he was also known to paint.

LARGER ART WORLD

Richard Levine was one of Young’s earliest patrons and helped him break into the larger art world. He also provided some early guidance to his work.

“When I bought the first pieces, [Purvis] said, ‘Oh, I’m going to take this money and buy canvases and I’m going to paint like Rembrandt,’ ” Levine recalls.

A notion Levine suggested he quickly put a stop to. Levine now has some of the few Young works painted on canvas.

Levine discovered Purvis Young while driving to work on the very highway built through Overtown, I-95. From the overpass he could see into the neighborhood — onto the street where Purvis had nailed hundreds of pieces on the outside walls.

“And then I read in the newspaper one day that the city was going to destroy all of that, throw it away, because they’re putting in a new housing project,” says Levine.

He drove down and bought about 80 pieces for a few hundred bucks.

Eventually, collectors like the Rubell family also started buying Young’s work. In one case, they bought some 3,000 pieces at once, the entire contents of his studio.

Though he never really quite “made it,” Young did achieve a certain amount of success before he died in 2010 at 67 years old.

His works are now part of the permanent collections of places like the Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Corcoran Gallery.

TODAY’S OVERTOWN

But in Overtown, the neighborhood where he found his makeshift canvases and his subjects, Young’s art never really found a place.

It was mostly white collectors buying his work and taking it out of the neighborhood.

Archivist Dorothy Fields says she hopes this exhibit will help change the neighborhood’s relationship with one of its own children.

“It’s important that community people come and see the success of what has come from this community,” she says. “From the streets of the community have come our own Rembrandt.”