Overtown: Reclaiming a Sense of Place

Written by Dorothy Jenkins Fields, Ph.D.

Originally printed in the Winter 2002 edition of Florida History & the Arts: A magazine of Florida’s heritage. Reprinted with permission of Florida Department of State, Division of Historical Resources. For further information, call 1.800.847.7278 or visit www.flheritage.com.

The community of Overtown is one of the oldest neighborhoods within the original boundaries of the City of Miami. Adjacent to downtown Miami, Overtown is bordered on the north by N.W. 21st Street, to the south by N.W. 6th Street, the east by N.W. 1st Avenue and on the west by 1-95.

Segregated by both custom and laws, it began as “Colored Town” at the turn of the 20th century. The area was assigned and limited to black workers who built and serviced the railroad, streets and hotels. The success of Miami’s pioneer tourist industry depended on the labor of black workers from the Bahamas and the Southern states. For more than 50 years, they were the primary work force in Miami.

Over time, immigrants arrived from Cuba, Haiti, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados and other countries throughout the Western Hemisphere. Their common heritage was their slave fore-parents, forced from Africa and left as cargo in various ports throughout America. Different cultures developed in the various ports and some languages changed, but the common ground for all was race. These skilled migrants and immigrants arrived with a determination to improve economic conditions for their families. In turn they helped build Miami and Miami Beach, a tourist mecca for others to enjoy.

When the decision was made to incorporate Miami as a city in1896, black men were used as voters but later disenfranchised. Since the required number of white male registered voters did not participate, black male registered voters were used to reach the number required by state law to form a new city. Nearly one-third of the men who stood for the incorporation of the City of Miami were black. After helping Miami become a city, the black incorporators lost their civil rights to existing public policy. Residents of Overtown in the late 1800s were subject to Black Codes, which, in the 20th century, became Jim Crow laws, restricting the civil rights of black people in every phase of life throughout the South.

In spite of these challenges, Overtown grew and developed into a vibrant community. As early as 1904, the official City of Miami directory listed businesses owned and operated by black people. These included general goods and services, a medical doctor, 26 laundresses, and several hundred laborers. Miami’s Colored Board of Trade was established as a clearinghouse for commercial and civic betterment. The Fourth Census of the State of Florida taken in the year 1915 records the population of Miami City at 15, 592. Of those, 5,659 residents were Negro. Their holdings in real estate and personal property were estimated at $800,000. Black women were not members of the Colored Board of Trade, but some were in business, including seamstresses, landlords, restaurant owners and a hat maker. Severl owned their own properties. Blacks living south of Miami in Coconut Grove and Lemon City to the north, would travel to Miami’s Colored Town for shopping, business transactions and entertainment.

Schools, churches and businesses flourished. Most of the goods and services in the community were produced by residents. There were many fine restaurants, a privately owned tennis court and several first-class hotels in Overtown. The Mary Elizabeth Hotel, built and operated by a black physician, Dr. W. B. Sawyer, Sr., was host to such notables as United States Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall; Congressman Adam Clayton Powell; labor leader A. Phillip Randolph; educator, Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune; Dr. Carter G. Woodson, “the father of Negro history,” and W E B. DuBois, and internationally known intellectual and author.

At least one national convention was held annually in Overtown, where hotel rooms, restaurants, cultural events and entertainment were in full supply. Repeat business brought by visitors helped stabilize the economy in the community, and promoted pride in a people who were self-motivated and self-sustaining.

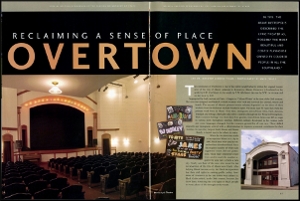

The Lyric Theater is the lone surviving building in the district known as “Little Broadway.” The Lyric opened in 1913 and quickly became the major center of entertainment for blacks in Miami. It was built, owned and operated by Geder Walker, a black man from Georgia. On October 16, 1915, the Miami Metropolis described the Lyric Theater as, “possibly the most beautiful and costly playhouse owned by colored people in all the Southland.”

White tourists and white residents also frequented “Little Broadway” to enjoy the entertainment, exotic foods and music, especially jazz and gospel singing. Local resident and entertainment promoter, Clyde Killens, was primarily responsible for bringing performers directly from the hotels and clubs of Miami Beach to Overtown. In the early days, black entertainers who performed on Miami Beach could not bed or board there because of restrictive social practices and racial segregation laws. After their last performances, these performers would cross the railroad tracks to Overtown’s hotels and night clubs.

Through the years, Overtown jammed to the sounds of Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong, Nat “King” Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., and many others. From Josephine Baker and Billie Holiday to Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne and Aretha Franklin – all found a welcoming audience in Overtown. Literary artists Langhston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, singers Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson, boxer Joe Louis and baseball great Jackie Robinson also frequented the area.

In the mid-1960s, Overtown began to lose its luster. Urban renewal and construction of two expressways tore the community apart. Today, Overtown is coming alive again. Efforts to preserve and restore historic sites, create housing and develop new mixed-use facilities proceed today with the support of many organizations and the dedication of community volunteers. Support for Overtown’s revitalization is derived from: the Overtown Advisory Board, the Overtown Empowerment Zone Assembly, the City of Miami and CRA, Metro-Dade County, Dade County Public Schools, the State of Florida, federal grants, St. John Baptist Church’s CDC, Greater Bethel AME Church’s CDC, the Knight Foundation, the LeRoy Collins Center, Greater Miami LISC (Local Initiative Support Corporation), and the Trust for Public Land.

Closed for four decades, the Lyric Theater was acquired by the Black Archives Foundation of South Florida in 1988, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in January of 1989 and reopened in 2000 after extensive restoration. Literary, visual and performing arts events take place throughout the year for tourists and residents in the 400-seat auditorium of this community centerpiece. The Black Archives, History & Research Foundation, Inc. is spearheading the development of the Historic Overtown Folklife Village, a two-block-area retail, cultural and entertainment district. The Lyric Theater is the anchor site of the Historic Overtown Folklife Village. Plans for the development of the Overtown Lyric Theater Complex include construction of a facility adjacent to the lyric, providing a welcome center, gift shop, banquet, community and meeting rooms, dance hall and catering kitchen. The complex will connect visitors to the 9th Street Pedestrian Mall, a transportation corridor linking Overtown to the bustling world of Greater Miami.

“This is a very historical area,” observed Professor John Hope Franklin, the James B. Duke Professor Emeritus of History at Duke University. “The very history of Miami is incomplete without the history of Overtown.” No doubt, the futures of Overtown and Miami are destined to be linked as well. Click to find out about places to dine, shop and explore in Overtown.

Click to view the this article as it appeared in the Florida & the Arts magazine